WILD STYLE1

Fashion, graffiti flavor

Rarely has a movement of counter-culture so quickly won the favor of the general public, and gained in respectability at the whim of fashion. “Street art” – we will use this catch-all term in the interest of simplicity, although it is used to encompass almost as many techniques as there are different works of art – has long since pushed its way through the doors of art galleries and been ushered into shopping centers.

According to urban legend, it was born in the streets of New York at the end of the 1960’s / start of the 1970’s. First invading subway wagons and stations, the facades of buildings and urban furniture, then drawing the attention of photographers and the media, street art rapidly took prime position in art galleries (Basquiat and Futura – which also used the pseudonym Futura2000 – exhibited from the start of the 1980’s), despite reticence in some quarters2.

It therefore comes as no surprise that commercial enterprises have sought inspiration from the movement, sometimes reproducing works identically without their author’s consent (and not always in good faith), while the streets of the whole world have become ever more covered with street art. Moreover, the artists themselves, as non-conformist as street art itself, are fully within their rights in asserting and earning from their monopoly in their creations – over and above the mere claim to authorship.

1/ Works of street art: “conventional” rights taken up in the powerful and sometimes uncontrollable wave of social media

1.1. Among the panoply of intellectual property protection available, it is of course copyright that will be the favored option to procure a monopoly for the authors of street art over their creations. The essential condition for the birth of such protection, which requires neither filing nor any specific formality (at least in France and in the signatory states of the Bern Convention) is that the work must be original. One can imagine this condition being met relatively easily for pictorial or artistic works, though the matter is frequently at the heart of disputes (it is standard practice in defense to challenge the originality of a work in an attempt to eliminate copyright protection)3.

1This title is borrowed from a documentary film from the 80’s, relating the birth of graffiti in the streets of New York. It is also the name of a “crew” of graffiti artists at the beginning of the 80’s, and of a style of graffiti: http://www.film-documentaire.fr/4DACTION/w_fiche_film/18746

2For example, in 1980, the Junior Council Co-Chair of the Museum of Modern Art de New York reportedly declared, “The people who graffiti ought to be shot at dawn”. This quotation, among others, appeared on the walls of the exhibition “City as Canvas” of the Museum of the City of New York, held in Spring 2014. See the museum website https://www.mcny.org/exhibition/city-canvas which also presents part of the history of the movement.

3On the subject of originality, see for example the preceding newsletter, by Fabrice Pigeaux: https://www.santarelli.com/en/wanting-to-be-the-author-of-a-protected-work-is-not-enough-or-when-a-lack-of-originality-catches-up-with-you/

Street art has one particularity linked to its nature: some have attempted to base pleas on the initial illicit character of the work (made, in many cases, without authorization from public bodies / the owners of buildings, even though this is not always true4) Thus:

- the works of the Space Invaders artist were considered as original, and thus protectable by copyright, by the Court of First Instance of Paris, in particular (and even particularly!): – on account of “the nature as urban media of said swimming-pool tiles sealed into the walls and the choice of their locations [which] bear the stamp of the author’s personality5.”;

- and so was the mural representation of an “Asian Marianne” by the artist Combo CK even though it had been made on a wall of Rue du Temple in Paris without prior authorization, and despite being ephemeral and having already disappeared at the time of the case6.

In the United States, the owner of the “5Pointz” site, well known to aficionados, was ordered to pay compensation to the artists for the destruction of works over of a single night, despite them being made on his property7.

Whether or not the work is licit does not therefore appear to be a condition for protection by copyright, and in the same way, the fact of being illicit ought not to compromise its protection8.

Nevertheless, it may be subject to limitation – particularly as regards moral rights and the component thereof relating to paternity In the case involving reproduction of the “Asian Marianne” by the artist Combo CK, reproduced without his permission and without mention of his name in a political campaign clip, the court of Paris noted that “the works of ‘street art’ made without authorization in a public space, may suffer detriment to their integrity, as well as to the paternity rights of their author, without their author appearing well-founded in complaining about this9.

4This qualification will of course not arise when the work is made entirely legally, either because the required authorizations have been obtained, or because a free space was made available to the artists. As an example, one may cite the numerous mural creations decorating the 13th District of Paris, under the aegis of the Itinerrance gallery in partnership with the District Town Hall (see for example https://www.parisinfo.com/visiter-a-paris/art-et-patrimoine-en-plein-air-a-paris/street-art-quand-l-art-fait-le-mur-paris/du-street-art-au-sud-de-paris), or a portion of Rue Ordener (Paris 18th), Rue Denoyez (Paris 20th) etc.

5Paris Court of First Instance, 3rd Chamber, 3rd Section, 14 November 2007, RG No. 06/12982

6Paris Court of First Instance, 3rd Chamber, 1st Section, 21 January 2021, RG No. 20/08482 (the artist indicated in an Instagram posting when the decision was handed down that an appeal had been lodged)

7See https://itsartlaw.org/2020/03/02/case-review-castillo-et-al-v-gm-realty-l-p/. However, in France, the supreme court confirmed that a penal qualification of degradation of property could not be dismissed by graffiti being protected by copyright Cass. Crim. 11 July 2017 – No. 08-84.989, in an action led by the Paris public transport operator, RATP.

8After all, the actual text of the Intellectual Property Code indicates that “the provisions of the present Code protect the works of authors for all works of the mind, whatever the kind, the form of expression, the merit or the purpose (Article L. 112-1)

9Paris Court of First Instance, 3rd Chamber, 1st Section, 21 January 2021, RG No. 20/08482. The press also mentioned a failed action by Space Invaders against two individuals caught by surprise tearing off one of his mosaics.

1.2. Moreover, filing for certain elements / logos / signatures etc. as a trademark may be envisioned, particularly when marketing operations or partnerships are planned, or when merchandizing is to be created and marketed (for example, stationery, clothing, accessories, etc.). Several artists have thus successfully crossed the line separating the artistic creation of clothing design, in the way Shepard Fairey (or Obey) did, who launched the line “Obey Clothing” after having pasted the face of André le Géant across the world for many years:

EU Trademark No. 008330698

Aside from the intention of commercial use, trademark rights cannot however make up for a lack of copyright or even for a copyright not asserted / expired, the desire to remain anonymous / to hide who is the author of the works and/or a total lack of intention for use as an indication of the origin of goods or services (as Banksy recently found out to his cost10).

1.3. Why not also envision claiming the civil liability of third parties copying a work of street art without the permission of its author? For example, the artist of Space Invaders obtained redress on this basis, even though infringement had not been found, for the use of pictograms reminiscent of his work in the PEUGEOT showroom on the Champs-Elysées11.

The artist Futura, who had instigated infringement proceedings against The North Face last January before the courts of California12, has also asserted not only copyright, but also acts of unfair competition, in a context in which he himself had established numerous partnerships with various brands:

Graphical comparison between the Futura logo and the trademark filed and used by The North Face, as appears in the artist’s writ of summons

Graphical comparison between the Futura logo and the trademark filed and used by The North Face, as appears in the artist’s writ of summonsThis nevertheless implies not only being able to identify any misappropriation (which is not always easy, when large promotional / commercial visibility operations are concerned), but also, for the artist, acting under his own name at the price of losing his anonymity, despite this being common, or even necessary in the milieu of street art (though in France, the court decisions available on line have been anonymized in advance).

1.4. Lastly, artists today have available to them a tool not to be underestimated: social media. From a legal point of view, social media may sometimes contribute to establishing evidence (see below), but their importance is above all practical. Their widespread use can enable artists, in an increasing number of cases, not only to obtain visibility but also to plead their cause directly with the public and/or draw attention to untoward users of their works, giving the artists leverage which can sometimes help them win their battles.

10The decisions concerning Banksy’s trademarks were commented upon in our previous newsletter, written by Isabeau Harretche: https://www.santarelli.com/en/all-may-be-lost-through-wanting-too-much1-or-when-applicants-are-reminded-that-bad-faith-has-its-limits-even-especially-in-trade-mark-law/

11Paris Court of First Instance, 3rd Chamber, 3rd Section, 14 November 2007, RG No. 06/12982

12Leonard McGurr, professionally known as Futura v The North Face Apparel Corp., Case No 2:21-cv-00269, US District Court for the Central District of California, summons dated 12 January 2021

The North Face for example has already announced that use of the logo associated with its “FutureLight” line would be brought to an end13, and appeals to boycott H&M were made after a mural by the artist Revok appeared in the background of one of its publicity campaigns (the group counter-attacked by asserting the illegality of the work, before a settlement was reached between the parties14):

The work by Revok15. Graphics from H&M’s campaign

In a similar but slightly older case, it was the platform given to the artist Ahol Sniff which made American Eagle react rapidly, after one of his creations appeared as a background to the photographs made for one of the collections of the mark, using both on the Internet site of American Eagle and in its stores:

Work by Ahol Sniff American Eagle’s graphics16

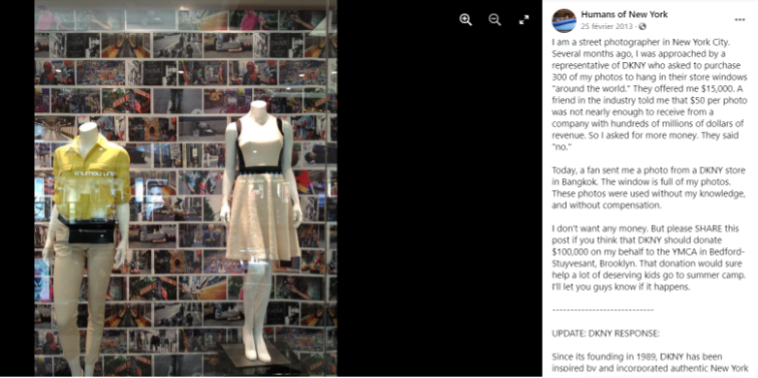

Sometimes, it can even be the community mobilized by artists through social media that will alert them to undesired use of their works. Thus, in February 2013, the photographer Brandon Stanton, known for his street photographs published on his blog “Humans of New York”, learned from one of his fans that the brand DKNY was using hundreds of his photographs in the window of one of its boutiques in Bangkok without his permission. He declared his case in a Facebook posting, calling his fans to exert pressure on the brand, which quickly reacted:

2/ The exceptions to such protection

2.1 As no intellectual property right is absolute, there are naturally exceptions to the protection of street artists, among which – in addition to the usual exceptions that are applicable to copyright – is for example that commonly known as “freedom of panorama”.

In this connection, Article L. 122-5 of the French IP Code, which lists the exceptions to the property rights of authors, has been amended by the addition of a paragraph 11 directed to “Reproductions and representations of architectural works and sculptures, permanently set up in public space, made by private individuals, with the exception of any commercial use.”

These last few years, this paragraph has sometimes been qualified as the “Instagram exemption”, because it gives authorization for anyone to take photographs of works of architecture and of art that appear in public space, and thus also for works of street art, and to publish them on the Internet (on Instagram for example). The Court of First Instance of Paris recently applied this exemption to a political clip distributed in the municipal election campaign of 2020, in which appeared a mural by the artist Combo CK, included in images filmed during demonstrations (despite the fact that the video editing drew attention to the work among a succession of different representations of “Marianne”, which might seem contestable)17.

13See the brand’s press-release: https://www.thenorthface.com/respectforartists

14See in particular the related comments in the article http://virtute.io/hm-street-art/ and the Instagram posting by the artist indicating that a settlement had been reached https://www.instagram.com/p/BnW29fVg-Ds/?taken-by=_revok_

15Photographs illustrating the article appeared in the Journal des Arts, see https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/actualites/fin-de-conflit-entre-le-street-artiste-revok-et-le-groupe-hm-139272

16Photographs illustrating the article which appeared on the Animal website, see http://animalnewyork.com/2014/street-artist-sues-american-eagle-outfitters-copyright-infringing-street-art-themed-campaign/

17Paris Court of First Instance, 3rd Chamber, 1st Section, 21 January 2021, RG No. 20/08482.

Of course, prior to the addition of this paragraph 11 to Article L.122-5, the French judges already had the discretion to apply what is known as the “background” empirical theory, by which the representation of a work located in a public space, when incidental to the subject concerned, is exempted from infringement18.

A parallel could be drawn with the “de minimis” copyright exception in the United States, which is applied when a work shown is secondary within another ensemble. This was the defense in particular employed by Mercedes, when street artists accused it of having reproduced their murals in a series of promotional photos posted on social media (the images have since been deleted from Mercedes’ Instagram account):

American law also specifically provides a “fair use” exception, enabling a balance to be achieved between copyright and other rights, such as freedom of expression or of information – as also do the exceptions of Article L.122-5 of the French IP Code, although the “fair use” exception can often be viewed as more flexible and malleable than our French exceptions.

2.2 All these exceptions however come up against a limit: commercial use (sometimes in good faith) of the reproduced works. Among the cases made public, but for which a settlement was reached, one may cite:

- the accusations of infringement made by the artists Reyes, Steel and Revok against Roberto Cavalli, who accused the brand of identically reproducing large parts of a mural made in San Francisco, on several items of its “Graffiti Girls”, collection, in 2014:

One of the comparative images presented on the site The World’s Best Ever19

- or those of the artist RIME, who accused Moschino and its designer Jeremy Scott of copying his graffiti-signature on a suit and a dress in the 2015 Fall/Winter collection (worn at the MET Gala):

Images of RIME’s logo-signature and of the creations of Moschino, as appearing in the artist’s writ of summons20.

18See for example the Court of Appeal, Paris, 4th Chamber, Section B, 12 September 2008, No. 07/00860 and the comment by Professor Pierre-Yves Gautier in Communication Commerce Électronique No. 11, November 2008, Étude 23

20Joseph Tierney v. Moschino S.p.A. et al, Case 2:15-cv-05900, US District Court for the Central District of California, summons dated 5 August 2015

- or for instance those of the artist Julian Rivera, in an action initiated against the retail chain Walmart and the TV presenter Ellen DeGeneres, who collaborated to produce a range of clothing displaying an imitation of his “love” logo-signature:

Photographs of Rivera’s logo-signature applied to clothing (top row) and of Walmart’s range created in collaboration with E. DeGeneres (bottom row), as appearing in the artist’s writ of summons21.

Of course, given that such examples are legion, this list is not exhaustive.

3/ Best practice: a checklist for artists, real-estate owners and user companies

And now, in concrete terms, what conclusions are to be drawn from this? What best practice should be adopted?

3.1. For the artists: even though this may seem contrary to your principles, be materialistic. You should avoid the pitfall of not keeping dated evidence, which is required to establish the ownership/paternity of rights, and even its originality. It is indeed incumbent on you to prove the rights you claim to possess, which involves being able to show with certainty that you are indeed the author of the work and that it is the result of your own creative process. In practice, this involves archiving your notebooks of sketches and preparatory research, which can sometimes bear an electronic date. The sending of certain drawings by registered mail, without opening the envelope, can also enable evidence to be preserved with an established date.

Lastly, social media can still be of importance: dated Instagram postings in which the artist Combo CK was identified have thus been considered as probative (combined with sketches, photos, etc.) to show the artist’s paternity, which was challenged by the opposing party

Screen-grab of the Instagram posting from @gaelic69 cited in the judgment

3.2. For real-estate owners: there is no rush. You will have to confront the thorny issue of the balance to be made between your material property (building, wall, etc.) and the immaterial property of the author over his work. As we have seen, the judges will not dismiss penal findings of the degradation of real estate on the grounds that the work is original / can be protected by copyright and the decision of last January, in the “Combo CK” case added its voice in saying that the artist’s moral right, to a certain extent, could be limited. You should not however have the possibility of commercially exploiting a work so made, even if Banksy voluntarily came to lay his stencils in your garden. As for cleaning/erasing the unauthorized creation from your wall, we would invite you to carefully study the issue of the qualification of the work and the identity of its owner (and to contact us).

3.3. For user companies: be fair. It almost goes without saying that the safest situation is to make sure of the creative process followed by your teams in-house, and to obtain the consent of the artist whose work you wish to use. Access to platforms such as social networks, today leads to the risk of “bad buzz”, calls for boycott, almost always to the cessation of commercialization of the accused products, and most often, to public excuses. Collaboration well thought out in advance will not only give legal security, but also provide promotion beyond your own networks, as the artist himself/herself will most often be involved.

21Julian Rivera v. Walmart Inc et al, Case 2:19-cv-05900, US District Court for the Central District of California, summons dated 29 July 2019

Our firm naturally is at your entire disposal to assist you on these very sensitive issues.

Nelly Olas is an Intellectual Property Attorney. Before joining the firm Santarelli in 2015, she worked as counsel – admitted to the bars of Paris and New York. She has more than 10 years of experience, and is the holder of a D.E.A. in literary, artistic and industrial property from Paris 2 – Assas University, as well as an LL.M. in Intellectual property from the University of Cardozo in New York.