In a previous article, we discussed the challenges faced by plant innovators when seeking patent protection for plant varieties in China. This does not, however, mean that innovative plant varieties are left without effective protection in the Chinese market.

In practice, robust and commercially meaningful protection can be secured through the Plant Variety Rights (PVR) system – also known as New Plant Variety Rights (NPVR) – which has been in place in China since 1997. Since then, the system has developed into one of the most active plant variety protection regimes worldwide, as demonstrated by recent filing statistics.

To strengthen it, the “Regulations on the protection of New Plant Varieties” have been amended and these new Regulations entered into force on 1st June 2025.

This article examines why the NPVR system has become a cornerstone of plant innovation protection in China. It highlights the scale of NPV filings in China compared with other jurisdictions and provides a practical overview of how to obtain NPVR protection and what commercial rights it confers under the revised regulatory framework.

Statistics

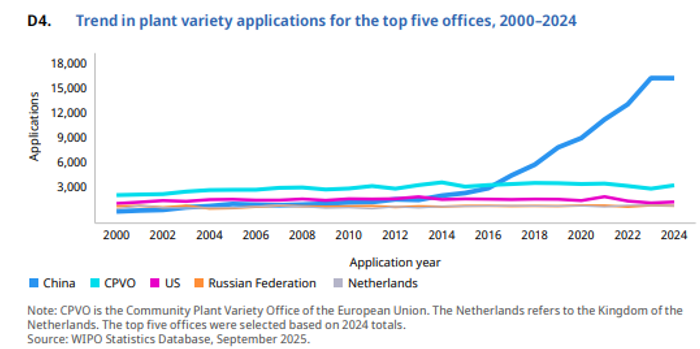

The efficiency of the NPVR system is clearly reflected in the impressive and steadily increasing number of NPV filings in China, which has, since 2016, become the country with the highest number of annual applications for agricultural plant varieties.

According to WIPO statistics, China was by far the leading jurisdiction for plant variety filings in 2024, with its authorities receiving 16,177 applications, representing 55.3% of all world-wide filings. The Community Plant Variety Office (CPVO) of the European Union ranked second with 3,268 applications (11.2% of the global total), followed by the United States (1,268), the Russian Federation (809) and the Netherlands (800).

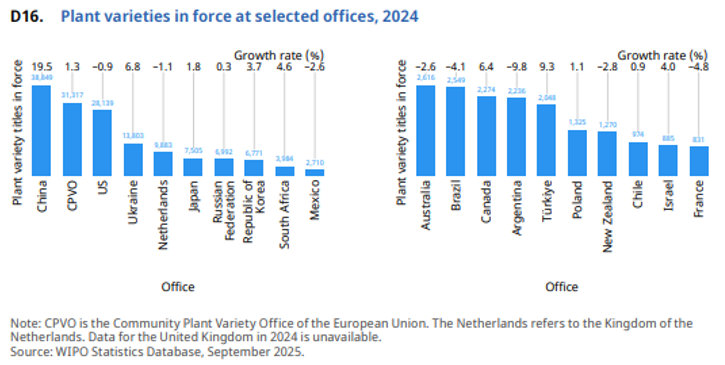

In terms of titles granted, China also led in 2024 with 6,675 titles issued. The next largest issuers were the CPVO (2,605 titles), the United States (1,242), Ukraine (878) and Japan (703).

At the global level, approximately 203,760 plant variety titles were in force at the end of 2024. China accounted for the largest number of active titles (38,849), followed by the CPVO (31,317), the United States (28,139), Ukraine (13,803) and the Netherlands (9,883). Notably, the number of active plant variety titles in China increased by nearly 20% in 2024 compared with 2023, while other offices experienced only modest growth, if any:

Although these figures relate to 2024, it is likely that this upward trend will continue in 2025, particularly in light of the new regulations that entered into force on 1rst June 2025, which are intended to strengthen the protection of plant varieties and shorten examination timelines, thereby better meeting the expectations of NPV right holders.

Get a NPV granted

What plant can be protected by a NPV ?

NPV protection is available in China only for genera or species listed in the two National Catalogs of Protected New Plant Varieties.

In 2020, these two Catalogs listed 397 genera or species, spanning grain crops, cotton, oil plants, fibre crops, vegetables, tobacco, forest trees, bamboo, fruit trees, ornamental plants, grasses, medicinal plants, edible fungi, algae, and others.

Where to file the NPV application?

Eligible applications must be filed in Chinese with either the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) or the National Forestry and Grassland Administration (NFGA) (formerly the State Forestry Administration), depending on the species for which protection is sought: MARA is responsible for 191 agricultural species, while NFGA handles 206 forestry and ornamental species.

How is the examination performed ?

After an application for a NPV is filed with the competent Chinese authority (MARA for agricultural varieties; NFGA for forestry varieties), it undergoes two examination phases.

The application first undergoes a preliminary examination, which lasts up to three months. During this phase, the examination fee must be paid and the authority verifies the following criteria (Article 28 of the 2025 Regulations):

Eligibility of the species: whether the species is included in the National Catalog of Protectable Plant Varieties (Article 14 of the 2025 Regulation);

Novelty (Article 15 of the 2025 Regulation:

- whether the propagating material of the variety has not been sold or otherwise commercialized by the applicant:

- in China, for more than one year prior to the filing date; or

- outside China, for more than four years, or six years in the case of vines, forest trees, fruit trees and ornamental trees (Article 15 of the 2025 Regulation);

- whether the variety has not been widely planted in practice;

- whether the crop variety has not been approved or registered for more than two years.

Acceptability of the variety denomination: the denomination must be distinctive, non-confusing and non-misleading, and must not fall within prohibited categories, such as names consisting solely of numbers, country names, well-known foreign places, names of international organizations, discriminatory terms, or terms contrary to public morality or law (Article 19 of the 2025 Regulation).

If the application passes this preliminary examination, it proceeds to a substantive examination, which is conducted on the basis of the application documents and, where necessary, field tests or on-site inspections carried out by designated testing institutions. As in Europe, this phase assesses the “DUS criteria” (Articles 16-18 of the 2025 Regulation):

- Distinctness: clearly distinguishable from all known varieties at the filing date.

- Uniformity: individual characteristics remain sufficiently consistent among the population, apart from predictable variation inherent to the method of propagation.

- Stability: characteristics remain unchanged after repeated propagation or across reproductive cycles

If all requirements are met, the authority issues a grant decision, publishes it, and sends the official NPV certificate.

How long does a NPV title remain in force ?

Under the most recent Regulations on the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, which entered into force in June 2025, NPV protection in China lasts 25 years for vines and woody plants (including forest trees, fruit trees and ornamental trees), and 20 years for all other plants (Article 35 of the revised Regulations).

This term of protection is calculated from the date of grant of the NPV title, unlike patents, for which the 20-year term runs from the filing date.

Enforce NPV rights

Recent extension of NPV’s scope of rights

The Chinese authorities established in 1997 a dedicated legal framework for the effective protection of new plant varieties under the “Regulations on the Protection of New Plant Varieties”. These Regulations have since been revised three times – in 2013, 2021, and most recently in 2025.

The owner of NPV right has the exclusive right to prohibit non-authorized third parties to produce, reproduce, sell, offer for sale, import, export, or store for any of these purposes. Importantly for NPV holder, this article has been greatly extended in the 2025 amendment, to encompass harvested materials and therefore all the production / exploitation chain of the seed industry.

This prohibition however does not apply if the variety rights holder has had a reasonable opportunity to exercise his rights over the propagating material (cf. article 7 of the 2025 Regulations).

Also, the scope of right has been recently extended to :

- “Essentially Derived Varieties” (EDVs) of the authorized variety, provided that the latter is not itself an essentially derived variety,

- Varieties that are not clearly distinguishable from same; and

- Other varieties produced or reproduced for commercial purposes using the authorized variety (Articles 7 and 8 of the 2025 Regulations).

The new Article 8 of the Regulations confirms that EDVs identification can be performed by using molecular detection and phenotypic testing, and possibly considers breeding methods and genetic relationships.

Exception to NPV rights

Under the UPOV Convention, protected plant varieties may be freely used for research and breeding purposes without the authorization of the right holder, reflecting the so-called “breeder’s exemption”. Similarly, NPV rights do not apply in China to the use of the protected variety for breeding or other scientific research (Article 12.1 of the 2025 Regulations).

Furthermore, according to Article 12.2 of the 2025 Regulations, NPV holders cannot prevent farmers to reuse harvested material for propagating purposes on their own holdings. In these situations, farmers are neither required to obtain permission from the NPV right holder nor to pay any exploitation fee. This last disposition differs from the EU regulation and French PVR system, where this “farmer’s privilege” only applies to 34 farm-saved seed species commonly used in agriculture. Moreover, in France, farmers producing and reusing one of these 34 seeds must, if protected by a PVR, compensate the holder by paying “equitable remuneration” (Article L623-24-2 IPC)(see our previous article.

Sanctions and damages

The first-instance court for civil actions involving NPV infringement is the intermediate people’s court located either where the infringement occurred, where the defendant’s provincial government is situated, or any intermediate court designated by the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) in that region. All second-instance NPV cases nationwide fall under the jurisdiction of the Intellectual Property Tribunal of the Supreme People’s Court.

Under Article 41 of the 2025 Regulations, these Courts are empowered to order the infringer to cease the infringing acts. In addition, they may confiscate the illegal gains derived from the infringement, as well as the propagating material of the protected plant variety held by the infringer.

The 2025 Regulations also introduce an important distinction based on the knowledge of the infringer. Under Article 45, where the infringement is committed without intent (i.e. unknowingly), no compensation liability shall be borne by the infringer. In particular, where a party processes propagating material for reproduction on behalf of others or sells propagating material without knowing that it relates to a protected NPV, damages may be excluded. However, the right holder may request that a license is agreed in the future, with license fees taking into account the type, duration, scope and other relevant factors.

By contrast, intentional infringement is subject to significantly strengthened financial sanctions under Articles 41 and 42 of the revised 2025 Regulations. In such cases, the levels of punitive fines have been substantially increased under the revised framework. Where the value of the infringing goods is less than RMB 50,000 (about 6000 euros), the fine may reach up to RMB 250,000 (about 30 000 euros). Where the value of the goods exceeds RMB 50,000, the fine may amount to five to ten times the value of the goods concerned. These increased penalties reflect the Chinese legislator’s clear intention to deter willful infringement and reinforce the effectiveness of NPV protection.

Two landmark decisions handed down in 2025 illustrate the growing effectiveness of enforcement in this area:

- In March 2025, the Envy® apple variety case resulted in an administrative fine of RMB 3.3 million (approximately EUR 400,000) in favor of the NPV holder HotResearch;

- In June 2025, the corn variety “NP01154” case led to an unprecedented fine of RMB 53.347 million (approximately EUR 6.4 million) awarded to the NPV holder Limagrain and its exclusive licensee Hengji.

These recent decisions demonstrate that NPV rights are no longer merely theoretical in China, but can be effectively enforced, including through substantial financial sanctions in cases of intentional infringement.

Conclusion

The recent overhaul of China’s plant variety protection regime marks a decisive step toward closer alignment with the UPOV standards. The revised framework not only strengthens the scope and duration of protection, but also significantly enhances the means of enforcement, with increasingly dissuasive sanctions that are now being effectively applied in practice.

This evolution has made the system increasingly attractive to foreign breeders and investors, who now benefit from a protection mechanism that is robust, predictable and commercially meaningful.

In this context, plant variety protection in China should be systematically considered whenever innovative plant material is developed or commercialized on the Chinese market.

February 2026